On the morning of September 4, 1844, Henry Rawlinson arose before dawn. Around him, the ancient city of Kermanshah still slept. The plains of Persia, modern-day Iran, stretched out for miles to the south and west. Rawlinson was exhausted. He had been riding hard for days across the desert from Baghdad. When he and his traveling companions had arrived in Kermanshah, “Our appearance on entering the town,” one confessed,

more resembled the arrival of a caravan of flour sacks than the advent of honored guests, for it was even difficult to distinguish the features of the party, so begrimed had we become from the dust heaped upon us.1

Despite his fatigue, Rawlinson had been too excited to sleep. To the east of Kermanshah, the first rays of the sun were beginning to shine on Mount Behistun, an enormous rocky outcropping, rising almost vertically from the plains below. High on the south-eastern side of the mountain, more than 300 feet above the plains, lay one of the world’s greatest mysteries—and a puzzle Rawlinson was determined to solve.

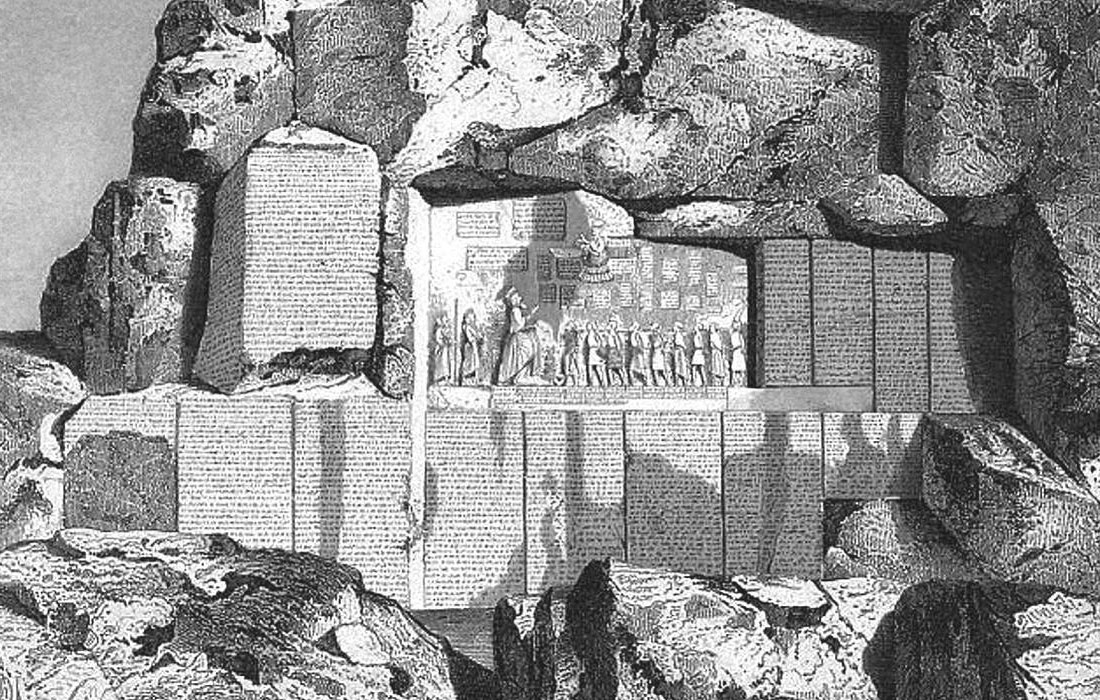

Carved into the cliffs was a colossal ancient engraving, 49 feet high and 82 feet wide. A Persian king, holding a bow, stood triumphantly with his foot on the chest of a prostrate man. In front of the king, nine other men were lined up, with their hands tied behind them. Surrounding the figures, three enormous inscriptions, battered by time but remarkably well-preserved, were cut into the limestone cliffs. No one had been able to read them for almost two thousand years.

A steel engraving of the Behistun Inscription published in 1863.2

The Behistun Inscription, as it has come to be known, was written in three languages: Old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite.3 The script was an ancient writing system that eighteenth-century Western scholars dubbed cuneiform, or wedge shaped. It was first developed in Mesopotamia during the early fourth millennium BCE and used up until at least 75 CE.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the languages of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia were mysteries. None of the hieroglyphs that adorned Egyptian temples, or the cuneiform symbols that captivated travelers to Persia, could be understood. The first real sign of progress came in 1822 when, after years of research, the philologist Jean-François Champollion cracked the hieroglyphic code. “Je tiens l’affaire!” he gasped—“I’ve done it!”—and fainted dead away.4

Champollion’s discovery was made possible by the Rosetta Stone—a black stele inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in 196 BCE by the pharaoh Ptolemy V. One copy of the decree was in ancient Greek, and two were in Egyptian scripts—demotic and hieroglyphic. By comparing a line in ancient Greek to its demotic and hieroglyphic equivalents, Champollion was able to work out the values of the previously unknown symbols and begin deciphering the lost languages.

Standing at the foot of Mount Behistun, Rawlinson thought he had found his own Rosetta Stone. If his hunch was right, the inscription on the mountainside was repeated in three languages. He could be looking at the means to understanding thousands of years of history. But there was a problem. The Rosetta Stone had been looted from Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte’s army in 1799—then looted from them, in turn, by the British. At 44 inches in height and weighing around 1,600 pounds, it was both accessible and transportable, meaning that the inscriptions could be copied easily and accurately. Clearly, the Behistun Inscription was not going anywhere. Peering through his telescope at line after line of characters, chiseled into what appeared to be an inaccessible cliff face, Rawlinson knew that even copying the inscription accurately, let alone deciphering it, would take every bit of ingenuity he had.

The story of Henry Rawlinson and the riddle of the mountain is a story about how knowledge is created. It does not have a clear beginning and its protagonists are largely unknown today. There is no eureka moment—no equivalent to Archimedes, naked and trailing bathwater, running gleefully through the streets of Syracuse. Yet it is also a story of world-changing discovery. The riddle of Behistun changed the way Westerners think about the past, and their place in history, forever.

The Fall

The rock of Behistun had haunted Rawlinson’s dreams for years. He first set eyes on it in the summer of 1836, when he was a young officer in the service of the British East India Company. European travelers had wondered about the inscriptions on the mountainside for centuries. But none had gotten close enough to record the cuneiform symbols accurately. After observing the inscriptions in 1598, the British adventurer Robert Sherley concluded that Behistun was a Christian monument. He was not alone in this assessment. In 1808, a French general and diplomat, Claude-Matthieu, Comte de Gardane, echoed Sherley’s view, claiming that the inscriptions depicted Christ and the apostles.5

Only in 1764, after the German explorer Carsten Niebuhr managed to copy a portion of the inscription, did scholars begin the battle to decipher it. By the early nineteenth century, thanks to the work of the philologist Georg Friedrich Grotefend, a few of the Old Persian symbols began to be understood. But in 1836, two of the inscription’s three languages, Babylonian and Elamite, were entirely unknown. And most of the inscription had still not yet been transcribed accurately.

Rawlinson was an unlikely scholar. To his friends, he appeared to be just another cheerful, hard-drinking junior officer—a little too fond of horses and cards, and a little too desperate to impress women. “The days all pass much in the same manner,” he wrote in his journal. “Parade at sunrise … play billiards, go out visiting, idle or sleep … out riding until dark, and in the evening sometimes cards.” “I am,” he remarked, “really quite sick of it.”6

As a child, growing up in Oxfordshire, Rawlinson had received a strong education in Greek and Latin. He learned to read Homer and Virgil almost as easily as Chaucer. In his first years of military service in India, he found that other languages came naturally to him too. Soon, the heady, blissful poetry of Persia was more of a thrill for him than the drunken dinners of his regiment. Junior officers were not often found swooning over the songs of the great Sufi poet Ḥafiẓ, so Rawlinson kept his new obsession to himself. But when the chance came for a posting to Persia, he jumped at it.

In 1836, standing in front of the Behistun Inscription for the first time, Rawlinson was not content to examine it through a telescope. He clambered up the sheer cliff face “three or four times a day without the aid of a rope or ladder,”7 and, as the summer went by, he painstakingly copied the Old Persian inscription, one symbol at a time. Balancing atop the cliff took, according to one French traveler, “the gymnastics of a lizard.”8 Overeager climbers were likely to find the descent even harder than the ascent and to reach the bottom in a tangle of limbs, “cut by the sharp angles of stones, completely torn and bloody.”9 But Rawlinson persisted. In July 1836, he wrote to his sister:

Despite the taunt which you may remember once expressing of the presumption of an ignoramus like myself attempting to decipher inscriptions which had baffled for centuries the most learned men in Europe, I have made very considerable progress in ascertaining the relative value of the characters.10

After a few months, Rawlinson returned to Tehran. He soon realized that almost all the discoveries he had been so proud of had already been made by other scholars, particularly Grotefend. Scholarly knowledge, at the time, circulated slowly and unreliably. Rawlinson had to rely on friends in Britain sending him the latest publications. Simple queries, such as whether anyone had figured out what a certain symbol meant, could take months to answer.

But unlike scholars in Europe, who were working from incomplete and inaccurate copies of the inscriptions, Rawlinson was on the spot—and he was confident that he would soon make discoveries of his own. But for now, he was painfully aware of how little he understood. Only a few symbols from one of the inscriptions had revealed themselves to him, and most of them were proper names.

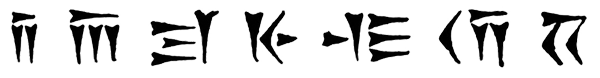

In an unknown language, the names of people and places are often the most straightforward elements to translate. Most cuneiform symbols required transliteration followed by translation. It was, for instance, necessary to transliterate the symbols for xšâyathiya, and then to work out that this word meant king. Proper names, in contrast, required only transliteration. The symbols for King Darius I,

could be transliterated as Dârayavauš, and be comprehensible without translation.

Before Rawlinson could make further progress, his quiet life in Persia was turned upside-down. One day in October 1837, he encountered a mysterious party of riders on the road from Tehran to the Afghan border. “[I]n cantering past them,” he later wrote, “I saw to my astonishment men in Cossack dresses.” Rawlinson trailed the party and, when they stopped for breakfast, he rode up to introduce himself, addressing the commanding officer

in French—the general language of communication among Europeans in the East—but he shook his head. I then spoke English, and he answered in Russian. When I tried Persian, he seemed not to understand a word.11

The officer, Ivan Vikevitch, was on his way to the court of Dost Mohammad Khan, ruler of Afghanistan, and was hoping to cultivate an alliance between Dost Mohammad and Russia.

That night, Rawlinson reached the camp of the Shah of Persia. The Russians arrived soon after him. Vikevitch now greeted Rawlinson in faultless French, observing, wryly: “It would not do to be too familiar with strangers in the desert.”12 Rawlinson, weary though he was, knew what he had to do. He climbed back onto his horse and rode more than 800 miles across Persia to Tehran as fast as he could, to bring the news to the British envoy, John McNeill.

Rawlinson had stumbled onto one of the opening moves of the Great Game—the contest between Britain and Russia for control of Central Asia. The news he brought of Vikevitch’s mission to Afghanistan electrified Britain and India. Amidst already-mounting tensions, the arrival of a single Russian officer so thoroughly alarmed the East India Company that, in 1839, it launched a full-scale invasion of Afghanistan. Thousands upon thousands of troops marched through the mountain passes and seized the country, deposing Dost Mohammad Khan.

Rawlinson was subsequently posted to the city of Kandahar and almost immediately saw that Britain’s grip on the country was far more tenuous than the men in charge realized. Unlike almost all the other British officers, he could speak the local languages. He made a habit of wandering the bazaars and riding in the countryside, listening to the rising anger against the British. It was risky work and he barely escaped assassination on at least one occasion.

When Rawlinson tried to point out that the British force was in danger and that an Afghan uprising was imminent, his superiors accused him of “taking an unwarrantably gloomy view of our position, and entertaining and disseminating rumours favourable to that view.”13

The disaster, when it came, was worse than even Rawlinson had feared. Caught between an Afghan uprising and the Afghan winter, the British commander in Kabul, Major-General William Elphinstone, decided to retreat to India. Heavily laden, full of the sick and the injured, and reduced to a crawling pace by the snows, the British forces were annihilated by the Afghans. Almost all of the column was either killed or taken prisoner. Only a few broken survivors crept back to India.

The war shattered Rawlinson. The world he had grown up believing in—where British superiority was as much a fact as gravity—had fallen apart around him. Nothing he had done, no matter how heroic, had been enough to prevent Britain’s defeat.

Throughout his time in Afghanistan, Rawlinson kept a few battered notebooks close to him—his records from Behistun. Even after losing almost all of his other papers, he still managed to preserve them. Now, in 1844, staring up at Mount Behistun once again, he was a different person to the optimistic young officer who had first passed this way a decade earlier. His resolve was stronger than ever. This time, he was not going to let the mountain’s challenge go unsolved.

He did not have much yet. But he did have a name—the name of a king: Darius.

The Name of the King

“I am Darius,” the Behistun Inscription begins, “the Great King, the King of Kings.” In Old Persian, the cuneiform reads: adam Dârayavauš xšâyathiya vazraka xšâyathiya xšâyathiy.

Darius I was indeed one of the greatest kings of Persia. He ruled the empire for 36 years, from 522 BCE until his death in 486. And, like many kings, Darius was a storyteller. Accounts differ as to how he came to the throne, though it certainly was not by legitimate means. He deposed and murdered his predecessor, then covered up his crime with a web of tales. Writing a century later, Herodotus told of an imposter-king, Gaumâta, who was assassinated by Darius and a group of noblemen.

Darius was a sharp and effective monarch. He stamped out rebellions throughout the vast Persian Empire. His rule stretched from the deserts of Egypt, to the borderlands of Europe, to the Indus Valley. He launched two invasions of Greece, much to the bemusement of the Persian nobility, who could see little in Greece worth conquering. The invading Persian army was finally stopped, in a last-ditch stand, by the Athenians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. Before Darius could send another, larger army to subjugate Greece once and for all, he died of old age—a luxury for a Great King.

Before he died, Darius gave orders for the history of his reign to be inscribed on Mount Behistun, where it could be seen by travelers on the royal road between Babylon and Ecbatana. In a world where texts could not be circulated easily, or copied without great expense and skill, inscriptions were often set up in conspicuous places so that the greatest number of people might see them. This inscription proclaimed Darius’s achievements to the world:

King Darius says: These are the countries which are subject unto me, and by the grace of Ahuramazda[,] I became king of them: Persia, Elam, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, the countries by the sea, Lydia, the Greeks, Media, Armenia, Cappadocia, Parthia, Drangiana, Aria, Chorasmia, Bactria, Sogdia, Gandara, Scythia, Sattagydia, Arachosia and Maka; twenty-three lands in all.14

Darius recounted his victories over the false king Gaumâta and other pretenders to the throne:

King Darius says: This is what I have done. By the grace of Ahuramazda have I always acted. After I became king, I fought nineteen battles in a single year and by the grace of Ahuramazda I overthrew nine kings and I made them captive. One was named Gaumâta, the Magian; he lied, saying “I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus.” He made Persia to revolt.15

Darius ended with a threat:

King Darius says: If you shall behold this inscription or these sculptures, and shall destroy them and shall not preserve them so long as your line endures, may Ahuramazda slay you, may your family come to nought, and may Ahuramazda destroy whatever you do!16

On the cliffside, Darius was depicted with his foot on the chest of the prostrate Gaumâta, with nine captive kings paraded before him.

The Climb

Rawlinson’s work at Behistun was fraught with danger. On at least one occasion in 1844, he found himself dangling from the cliff face, hanging onto the rocks for dear life. While attempting to reach the Elamite translation for the first time, his ladder gave way. He inched his way toward a narrow ledge and the promise of safety, watched by his terrified companions and by the impassive stone eyes of Darius, above. Far below him, he could hear his ladder, now reduced to its component parts, “crashing down over the precipice” toward the plains.17

But Rawlinson was undeterred. Slowly, methodically, he worked his way up and down the inscriptions, tracing the words of Darius, one symbol at a time. The ledge on which his ladder rested was, at times, barely a few inches wide. One wrong move would send him tumbling backward into space. From dawn until dusk, in the punishing summer heat, he balanced on his ladder. The very highest inscriptions had to be copied by

standing on the topmost step of the ladder, with no other support than steadying the body against the rock with the left arm, while the left hand holds the note-book, and the right hand is employed with the pencil.18

The cliff face was warmed by the heat of the sun and by mid-afternoon, standing beside it must have felt like standing next to an open oven.

The beauty and complexity of the gigantic inscription often left Rawlinson breathless. At the time, few appreciated the immense sophistication and advancement of the ancient Persian Empire. Western scholars, like the ancient Greek historians upon whom they relied, tended to dismiss the Persians as barbarians. But here, Rawlinson could see, was something almost entirely unknown to Western scholarship. A rich and wondrous culture was emerging from the shadows of history for the first time in centuries.

Where he could not reach the inscription himself, Rawlinson paid enterprising local boys to scale the cliff and copy it for him. For this task, he gave them not pencils and paper, but wet papier-mâché. When the boys reached the inscription, they would press the mass of papier-mâché to the side of the cliff, squeezing it into the hollows of the inscription. The resulting paper “squeezes,” as Rawlinson called them, provided near-perfect casts of the cuneiform characters.

As the light was fading on September 10, 1844, Rawlinson reluctantly brought his work copying the inscription to a close. “[T]he ladders were cast headlong from the rock into the plain below, to prevent mutilation of the tablets. They were shivered into a thousand pieces.”19

The Riddle

The first story about the invention of writing comes from ancient Mesopotamia. The legend of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, which was transcribed around 1800 BCE, tells of a messenger who was so overwhelmed by what he had to remember that he was not able to utter a single word of his message. So, the ruler “patted some clay, he put the words on it as on a tablet. Before that time, words put on clay had never existed.”20

Yet even in the ancient world, few knew how to read cuneiform. Kings struggled to understand the words set down in their names. And for all his adventures, Rawlinson still had little idea what the mysterious symbols meant. Understanding them would be an even more difficult task than his ascent of the cliff face in Behistun. At the time, some scholars thought that cuneiform symbols acted like an alphabet: a symbol was equivalent, for instance, to the letter “a,” and another to the letter “b.” This was, in fact, not true.

Two things made Rawlinson’s task particularly hard. First, cuneiform was a script, not a language. It could be used, as it was at Behistun, to write in a number of ancient Mesopotamian languages, including Old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite, among others. Even the successful translation of one cuneiform inscription would not necessarily help in translating another, unless it happened to be in the same language. The second problem was that cuneiform was not an alphabet. The symbols denoted syllables, rather than letters, and had multiple meanings.

In 1851, Rawlinson was appointed as the British consul general in Baghdad. He settled happily into life at the British Residency, on the banks of the Tigris River. It was an idyllic setting,

[b]y far the pleasantest place in Baghdad … a beautiful old house built round two large courtyards and having a long frontage to the river. There is a delightful terrace overlooking the water, with an alley of old orange trees and a kiosque or summer-house and steps, leading down to a little quay where the consular boats are moored. Inside, the house is decorated in the Persian taste of the last century … with deep fretted ceilings, walls panelled in minute cabinet work, sometimes inlaid with looking-glass, sometimes richly gilt. Only the dining room is studiously English.21

Rawlinson worked in the summerhouse at the end of the Residency’s garden, which was built over the Tigris. He designed an ingenious contraption to keep it cool, a waterwheel “which poured a continuous stream of Tigris water over the roof.”22 There, he would spread out his notebooks and papier-mâché molds, and puzzle over them for hours, trying out one method after another to decipher the symbols, as the sun climbed higher and higher in the sky and the noise and laughter of Baghdad drifted through the garden.

Rawlinson’s first task—to complete as full a transcription of the Behistun Inscription as possible—was accomplished easily enough. But after that, there were few clues to guide him. Scholars had successfully deciphered some of the symbols, mostly royal titles and proper names, which appeared in standardized forms in multiple inscriptions. Some bilingual texts had also been discovered, written in cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs. Once translated, the hieroglyphs allowed the corresponding cuneiform to be understood. It was a beginning, but only a beginning.

A sketch of the Behistun Inscription published in 1861.23

Rawlinson knew that languages, like people, have family trees based on resemblances: “family” in English, “la famille” in French, “die Familie” in German, and “la famiglia” in Italian all trace their roots back to the Latin “familia.” Rawlinson’s hope was that the languages he had devoted years to learning—including Persian, Avestan, and Sanskrit—would help him. With any luck, resemblances between them and the languages of the Behistun Inscription would help him unlock the text.

Rawlinson’s notebooks trace his struggle. The cuneiform symbols themselves appear faintly at first, traced in pencil, then written over in pen, one symbol at a time, as Rawlinson became more confident of their shapes. Some lines are scribbled over and rewritten. Some are mostly gaps. “The last lines are wholly illegible,” Rawlinson confessed.24 Then slowly, gradually, his translations begin to take shape. Names emerged first, starting with Darius, followed by more and more words. Each time Rawlinson wrote out the Behistun Inscription, his translation was fuller and more accurate. At times, his handwriting judders and crabs, and begins to look more like the symbols he was trying to decipher than the flowing cursive script he had been taught as a schoolboy in Britain.

Rawlinson completed and published a translation of the first of Behistun’s three inscriptions—the Old Persian—in 1846.25 The next year, he returned for the others. From his camp beside the mountain, he wrote to a friend and colleague in London, Edwin Norris of the Royal Asiatic Society:

I am delighted to be able to inform you that on my return to this place about ten days back with renovated health and spirits, I discovered a considerable [emphasis original] portion of the Babylonian translation of the great inscription to be legible. I immediately set to work on it, taking in the first place two careful and independent copies with the aid of a powerful telescope from a perch on the opposite precipice.26

Rawlinson managed to persuade two local men to scale the precipice and make more papier-mâché casts of the inscription.

Yet the more success he met with, the more Rawlinson realized how much work lay ahead. “My Babylonian paper, when completed will be after all but a mere brick [emphasis original] in the edifice,” he wrote ruefully to Norris.27 But, one day at a time, symbols were giving way to words, and words to ideas. For the first time in over two thousand years, a Persian king was speaking.

Of course, as this was the age of nationalism and empire, not everyone agreed that Rawlinson was the first to decipher cuneiform. There were other contenders, such as the Franco-German Assyriologist Julius Oppert, and Edward Hincks, an irascible self-taught genius and rector of Killyleagh in County Down, Ireland. Hincks and Rawlinson made many of the same discoveries simultaneously and, naturally, each suspected that the other was a charlatan and a plagiarist.

By the end of the 1840s, Rawlinson was still struggling with the two most difficult languages of the Behistun Inscription, Babylonian and Elamite. He confessed to Norris that he had “no heart to bear up against such repeated disappointments,” and had been “a hundred times tempted to throw the whole of my papers into the fire.”28

Then Rawlinson realized what he had been missing for almost fifteen years, and what no one else had yet understood: each cuneiform character could have multiple meanings. Before he could hope to decipher the languages, he would need to pin down all those variant readings for each character, “all of which must be identified before the fundamental task of constructing an alphabet can be considered to be satisfactorily accomplished.”29 It was an exhausting realization. In an instant, it added years to his task. But it was also a revelation. “Glimmerings of light are pouring at all points,” he wrote to Norris.30 Soon, his notes were piling up once again. He sent Norris

a sheet of syllabarium for your quiet examination … I have only put down those ideographs which have either one or the other of the phonetic readings—my note book contains at least 100 more of which the phon[etic] powers are wanting or in fragments.31

At long last, the solution to the riddle of Behistun appeared to be within reach.

In 1853, Rawlinson published a Babylonian translation, completed independently of work by Hincks, Oppert, and Henry Fox Talbot.32 He then passed on his casts to Norris, who finished and published the Elamite portion in 1855.33 Elamite remains, to this day, a language isolate—a language with no known relatives—which made its translation especially difficult.

The Last Question

Before Rawlinson could celebrate the completed translation of the Behistun Inscription, there was one final test. When he returned to London in 1855, Rawlinson found that his discoveries had made him a celebrity. His insights into cuneiform, along with the archaeological discoveries of Austen Henry Layard in the ancient cities of Mesopotamia, had created a frenzy in Victorian Britain for all things Assyrian. The arrival of Layard’s finds at the British Museum was covered breathlessly in the press. Fashionable ladies dressed as Babylonian queens. Even Queen Victoria ordered Assyrian-themed jewelry—including a “turquoise and brilliant Nineveh brooch”—for a state visit to Paris.34

Now, the Royal Asiatic Society proposed a test to see if the mystery of cuneiform had truly been solved. Scholars were invited to submit sealed translations of one specific inscription, a newly discovered piece from the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I, dating from around 1100 BCE. The translations would be opened by a specially appointed committee. If the translations agreed, then the mystery could be said to have been solved. Four scholars submitted translations: Rawlinson, Hincks, Oppert, and Talbot. When it came time for the translations to be scrutinized, London held its breath.

Things did not start well. Talbot’s translation was a mess. Oppert’s version barely resembled English in some places. Hincks had only completed part of the set inscription and complained that he had been treated unfairly. But the closer they looked, the more the committee found that, in all important respects, Rawlinson, Hincks, and Oppert agreed almost exactly. After almost two thousand years, the mystery was a mystery no more.

And, of course, the work was just beginning.

Today, hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets, seals, and cylinders languish unread in archives across the world. Decipherment is still so complicated and the skills required are so challenging to develop that only a small fraction of cuneiform tablets discovered during the nineteenth century have been translated, let alone published.35

Despite how much work remains before scholars can truly understand ancient Mesopotamia, there is no doubt that Rawlinson’s discoveries changed the world. When the great masterpiece of Mesopotamian literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was deciphered in the 1870s, Victorian scholars got the shock of their lives when they came to one particular story.

In Gilgamesh, the god Ea commands Utnapishtim to build an enormous boat, so that he will survive a great flood which is about to consume the earth. The boat is loaded with “all the animals and beasts of the field.” Then the flood comes, and as it rolls across the earth, the seas fill up with bodies and the gods weep. When the storm clears, the boat comes to land atop a mountain. Utnapishtim emerges cautiously, to find that the rest of humanity has turned to clay.

To the Victorians, the story of Utnapishtim sounded eerily similar to that of Noah in the Old Testament. Yet Gilgamesh was composed centuries before the earliest datable version of the story of Noah. At a stroke, almost everything that many Victorians thought they knew about the age of the world, and the relationship between Eastern and Western cultures, had to be reassessed.

At one point, while he was in Baghdad, Rawlinson was convinced that he had “found Noah and his whole history in the inscriptions.”36 But what he had actually found was something even more remarkable—a discovery which, one long-silenced voice at a time, changed how we look at the past, forever.