To the editors:

Lively discussions and controversies have arisen from the contrasting gradual and emergent explanations for language’s evolution. In this letter, I would like to add further support for the view that the language faculty could not have evolved gradually.

In their essay, Robert Berwick and Noam Chomsky reply to Cedric Boeckx’s criticism of their book Why Only Us and defend the view that the language faculty comprises a distinctive human phenotype that resulted from a small rewiring of the brain.1 They illustrate how a minimal change in a computational system may have broad consequences on the overall generative capacity of that system, much like a small rewriting of the brain may have led to the rapid emergence of the language faculty. Berwick and Chomsky point to a common confusion in conventional evolutionary theory between the cognitive ability for language and its externalization. They also note Eric Lenneberg had foreseen the inherent difficulty in any evolutionary explanation of human language:

We can no longer reconstruct what the selection pressures were or in what order they came, because we know too little that is securely established by hard evidence about the ecological and social conditions of fossil man. Moreover, we do not even know what the targets of actual selection were. This is particularly troublesome because every genetic alteration brings about several changes at once, some of which must be quite incidental to the selective process.2

Language is a generative system that yields unlimited production from finite means. The discrete infinity of language is problematic for any evolutionary explanation. How is it possible for this Basic Property of language to have evolved gradually? Riny Huijbregts proves that this is a logical impossibility.3 He summarizes the arguments for two conflicting views on the discrete infinity of language: language emerging as infinite, and language emerging as finite proto-language and then evolving to infinite language.4 He shows that the computational system underlying human language could not have been reached gradually because the infinite productivity generated by such system cannot be reached stepwise.

In evolutionist explanations of language, proto-syntax is an intermediate state of development: the pre-syntactic one-word stage leads to the proto-syntax two-word stage, which leads to modern syntax. Unsurprisingly, there is little consensus on what the properties of proto-language could be. For Derek Bickerton, proto-language had a large vocabulary, but no internal syntax.5 For James Hurford, proto-thought had something like predicate calculus, but no quantifier or logical name.6

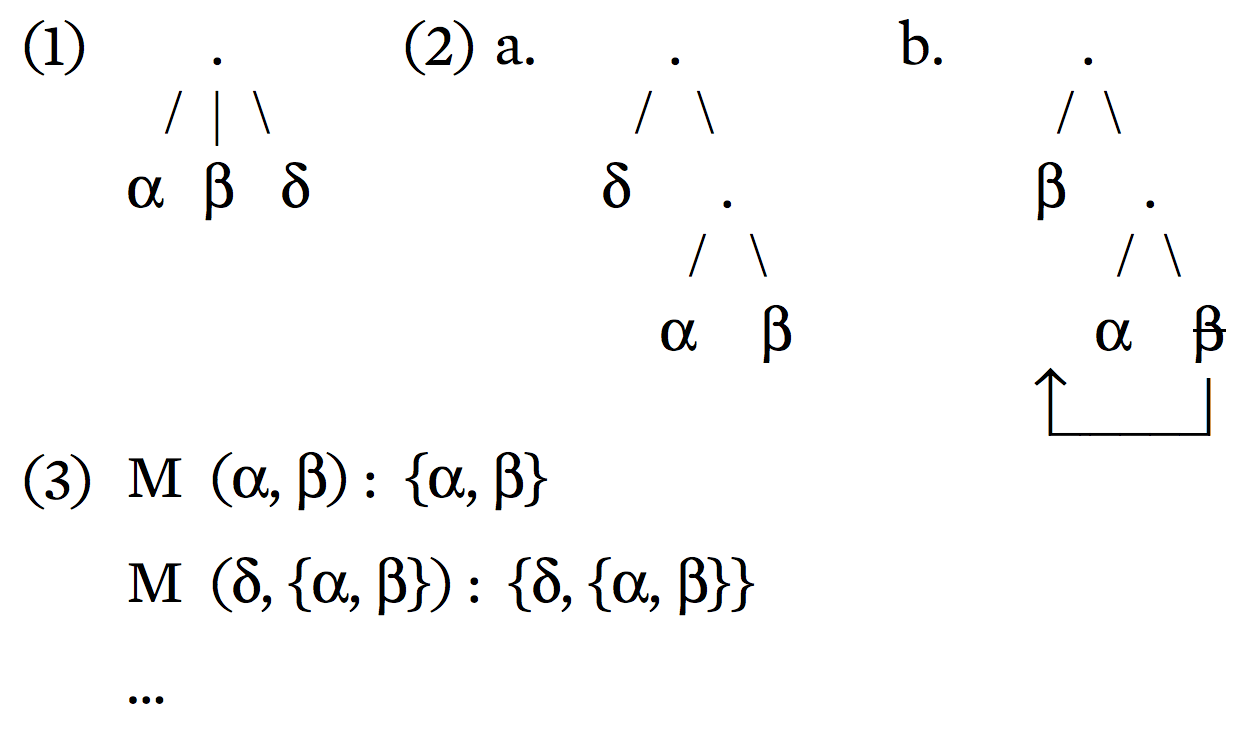

Ray Jackendoff takes proto-language to be derived by proto-Merge, the precursor of full-fledged Merge.7 Proto-Merge would be an n-ary operation that generates flat concatenation or adjunction structures (Figure 1). It could not generate hierarchical structures (Fig. 2), which instead are derived by Merge (Fig. 3). Merge is a binary operation. It takes two syntactic objects, represented by variables α and β (Fig. 2), and derives a set.8 This operation is recursively unbounded. That is, it may reapply indefinitely to its own output. Unbounded Merge recursively combines two syntactic objects (Fig. 2a). It may also displace to a higher position in the hierarchical structure an object that has been previously merged, leaving the lower copy of the displaced constituent unpronounced (Fig. 2b). The syntactic derivations may also include silent constituents that do not result from their own displacement: for example, categories occupying in the position of α and β (Fig. 2). Silent constituents are derived by unbounded merge, interpreted at the semantic interface, but not externalized at the sensory-motor interface. This asymmetry is a feature of language design not taken into consideration in conventional explanations of language evolution, which are mainly focused on externalization.

As there are no recordings of proto-language, believers in the gradual evolution of language have attempted to identify empirical evidence for a previous evolutionary stage in modern languages. Two-word expressions with irregular grammatical properties, such as English exocentric VN compounds dare-devil and pick-pocket, have been identified as fossils of proto-language.9 According to Ljiljana Progovac and John Locke,

While these compounds violate several rules and principles of modern syntax, their structure, as well as their persistence, do provide some continuity with modern syntax. If so, then the syntax that supports their formation (proto-syntax) may have facilitated a transition from a pre-syntactic (one-word) stage to modern syntax.10

Such analyses are irrelevant to the problem of language evolution, given that the language faculty is an unbounded recursive system and that the gradual evolution of a finite language into infinite language is not a logical possibility. The notion that constructions like VN exocentric compounds are remnants from proto-language is nothing more than speculation. The alleged absence of a principled, Merge-based analysis of these constructions is not proof that they are fossils of proto-language. And in any case, such an analysis is already available.

VN exocentric compounds are not derived by proto-Merge and thus are not remnants of a finite proto-language.11 Their underlying hierarchical structure is derived by full-fledged Merge and includes unpronounced constituents. This does not come as a surprise. The phenotypic property of the human language faculty is an unbounded hierarchical assembly of syntactic objects with two interfaces. The hierarchical structures are derived by the computational procedure of the language faculty and are interpreted by the semantic system and by the sensory system. Given this asymmetry, the externalization of a linguistic expression is not isomorphic to its semantic representation. Interface asymmetries are pervasive in language and are part of language design.12 They are expected in the derivations of any linguistic expression, including one-word expressions.

One-word expressions, such as here and there, in expressions such as I stayed here and I went there, include an unpronounced locative or directional preposition at or to.13 In English, this preposition is omitted and is interpreted only at the semantic interface. This is also the case in Italian with qui (“here”) and li (“there”). The directional preposition a (“at” or “to”) is sometimes pronounced in varieties of Italian spoken in southern Italy, where aecche (literally, “at here”) and alocche (“at there”) closely relate to their Latin counterparts, ad hic and ad locum.14 This illustrates that the hierarchical assembly of linguistic expressions leading to the semantic interface may not coincide with the externalization of these expressions at the sensory interface.

The hierarchical structure derived by full-fledged Merge underlies any linguistic expression. A conventional evolutionary theory of the language faculty fails to distinguish the unbounded recursive assembly of syntactic objects from their externalization. The latter is subject to variation, contrary to the former, which is the human-specific phenotypic trait under investigation.

Progress has been made in characterizing the human specific phenotypic trait.15 This progress logically excludes any evolutionary explanation of the human language faculty, because of the impossibility of attaining the infinite generative system of the language faculty stepwise. The alleged proto-Merge analysis of apparently simple and irregular expressions is a stipulation and is irrelevant to the evolvability of recursive languages. An analysis based on full-fledged Merge of apparently simple and irregular expressions in conjunction with the asymmetry of the interfaces offers a deeper explanation for the human capacity for language than evolutionary proto-Merge analyses.

Further work on the biological underpinning of infinite languages, unbounded Merge, and design features such as interface asymmetries may lead to a deeper understanding of the language faculty and its emergence in Homo sapiens.

Anna Maria Di Sciullo

Robert Berwick and Noam Chomsky reply:

Anna Maria Di Sciullo’s general point is well-taken. Apparently simple and irregular expressions can be analyzed using full-fledged Merge and empty elements, without any new stipulations. This scientific parsimony is exactly why, at least for such cases, there is no need to posit some other operation alongside Merge, no matter what its origin. Even using the term proto-Merge lends it too much credibility. Proto-Merge is not even definable, and it does not simplify the evolutionary picture. For instance, there is no way to move from Jackendoff’s n-ary operations to Merge, even putting aside the question of whether an n-ary operation is simpler than Merge.

The examples of linguistic fossils that have been cited by Jackendoff and others are linguistic forms, such as daredevil. The latter term arose only in the early 1700s; nobody seriously suggests it is really 100,000, or more, years old. What about claiming that the n-ary operation itself is a fossil? As far as we know, Jackendoff does not suggest this, but if he did, it would be meaningless—like saying that Merge is a fossil, or the human heart is a fossil. We are not supposing that new operations were devised 20,000 years ago. As far as we know, the language faculty has remained intact since before the separation of modern humans when they exited Africa.

Are there any signs of an n-ary operation today? The only close candidate is unbounded, unstructured coordination: “I met someone young, tall, eager to go to college, ....” But n-ary operations are not the right system to describe examples like these. We have to account for the fact that the elements in such examples share a category: “young” and “tall” are both adjectives. This again begins to sound something suspiciously like Merge. We think this hunch is on the right track, but we do not have space to go into detail about it here. There is no version of proto-Merge apart from full-fledged Merge.